History

At the Head of the Lakes

With its spectacular location at the westernmost tip of the Great Lakes, Superior has long been a destination and hub for human activity.

For centuries, Lake Superior’s shores and the surrounding area have been home to the Ojibwe people, also known as Anishinaabeg or Chippewa. Life at these headwaters offered ample chances for hunting, fishing and gathering of food and medicine.

Then as now, that had everything to do with being near the big lake (Gichigami), the St. Louis River (Gichigami-ziibi) and Nemadji River (ne-madji-tic-guay-och). These waters shaped the unique geology of the region, creating the likes of Wisconsin Point, a 3-mile sandbar peninsula where local Ojibwe people historically lived and a burial ground is located today. Travelers often arrived using the Bois-Brule St. Croix River portage.

This ancient path, used by indigenous people for centuries, connects waterways that link Lake Superior and the Mississippi River. For early European explorers, the trail opened eyes to the potential of a place that would come to be called Superior.

French travelers exploring the Great Lakes in the 1600s called the westernmost lake “Superior” on account of its higher elevation. And in 1854, the name was applied to the lake’s newly formed westernmost town: Superior, Wisconsin. That’s a year when life changed dramatically for the Ojibwe people (Treaty of 1854) and when Europeans began dramatically changing the landscape. Ground had been broken on the Soo Locks in Michigan, connecting Lake Superior with the lower Great Lakes. It allowed ships to travel here from far and wide, ushering in a whole new era.

The first of two Twin Port cities to be founded, Superior was known as the place “Where Sail Meets Rail.” Together with Duluth, Minnesota, which shares a natural harbor, Superior experienced cycles of boom and bust growth over the course of decades in the late 1800s.

Investors came seeking fortunes from the region’s old-growth timber and iron ore. Immigrants from places like Finland, Norway, Germany, England, Ireland, Italy and beyond poured into the region for a better life — taking jobs at the docks, boats, factories, logging camps, mines, mills and more. Ships came and went with cargo and travelers. At one point, Duluth Superior harbor was among the busiest in the United States. With railroads connecting to the Great Plains, the Iron Range and beyond, this was a place where abundant natural resources, commerce and people came together and reached out to the world. The legacy of that Gilded Age is on display today in the stately historic architecture of homes and museums like Fairlawn Mansion. In businesses and city blocks like Tower Avenue. And in stories shared at museums and events across the region.

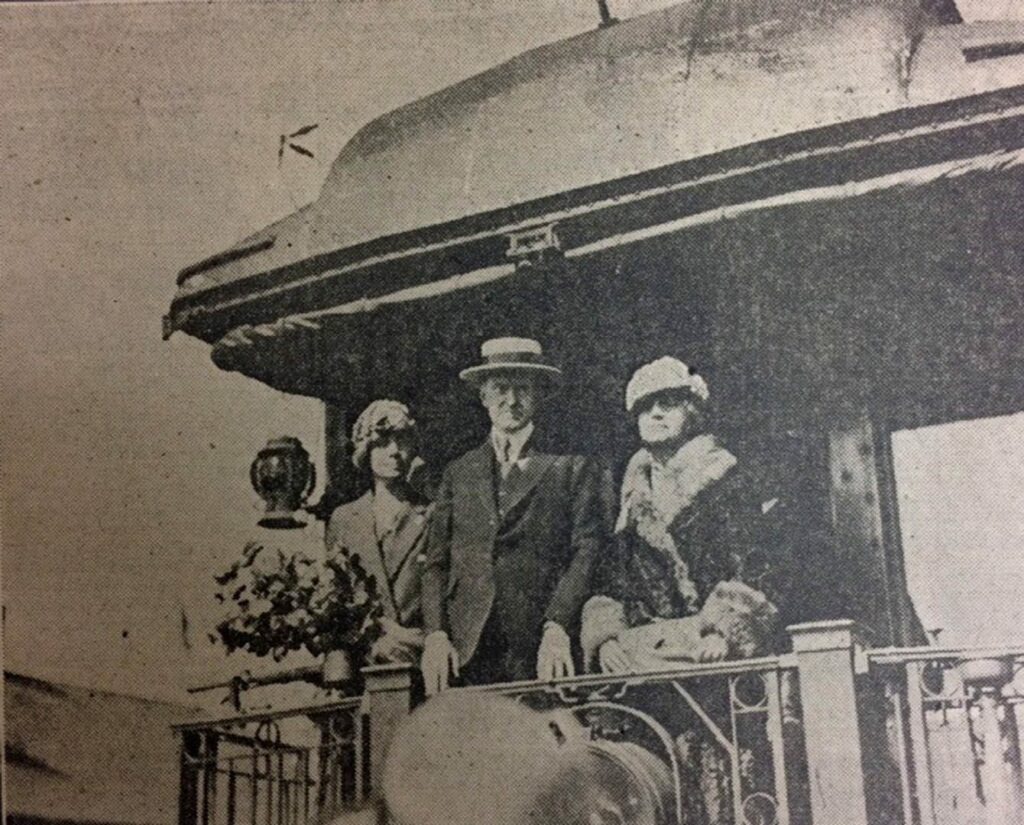

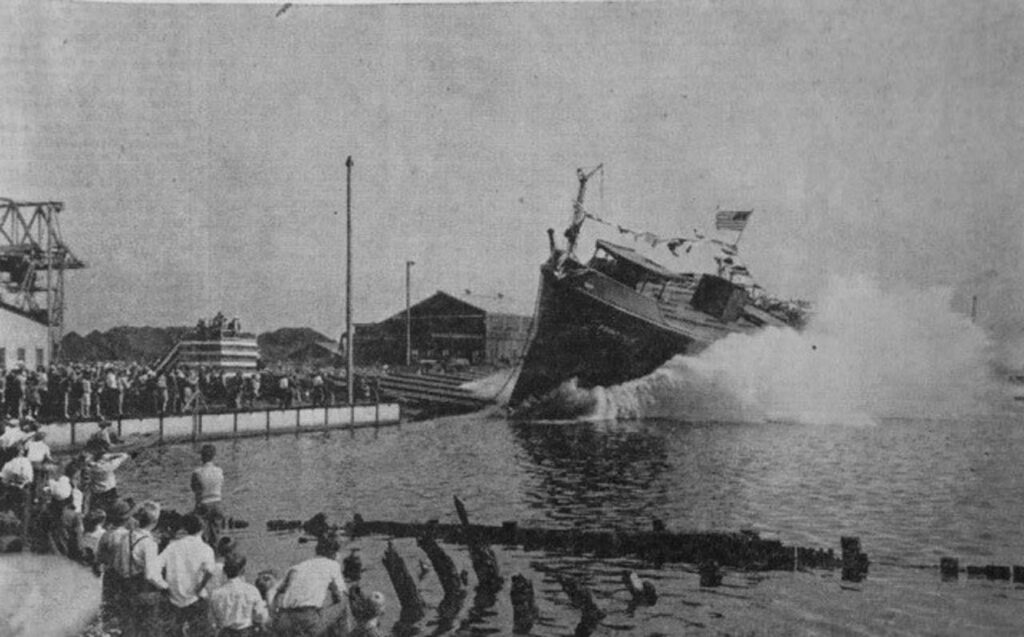

Shipbuilding and repair were big, and are still on display at Fraser Shipyards to this day. When built in 1890, the Superior shipyard was the largest dry dock on the Great Lakes. Dozens of ships were built for WWI and another 200 were built for WWII in the Twin Ports. At one point, the world turned its eyes here as the “The Quints,” Canada’s famous Dionne Quintuplets, came to christen new ships for the war effort.

That tradition of maritime excellence started with Scottish Captain Alexander McDougall, who founded what would become Superior Shipbuilding so he could produce his new whaleback steamship, an innovative design for hauling bulk freight like grain and iron ore. The last active whaleback, the SS Meteor, ran aground in 1969 after 73 years of service. With severe hull damage, the old steamer was returned to its birthplace in Superior, where it is now a museum.

The iconic, 70-foot-tall Superior Entry Lighthouse on Wisconsin Point was built in 1913 to guide maritime traffic from Lake Superior into the Superior Harbor and Allouez Bay. The largest freight ships on the Great Lakes have passed by that pier thousands of times while traveling to and from Superior’s iron ore docks. These massive concrete and steel structures, the largest installation of their kind in the world, loaded ships with ore hauled from Minnesota mines. More than 1 billion tons of ore passed through the docks, which saw their heyday in the 1950s.

It’s also where the SS Edmund Fitzgerald departed on its last voyage. On November 9, 1975, the 729-foot “Fitz” — then the largest ship on the Great Lakes — left the docks on a beautiful day, only to sail into one of the worst storms ever to occur on Lake Superior. The Fitzgerald was the largest and most recent shipwreck on the big lake they call Gitchee Gumee, taking the lives of all 29 mariners who were aboard. It’s a harrowing reminder of the power and unpredictability of Lake Superior, where an estimated 550 shipwrecks have occurred. And where dozens of lighthouses were built in an effort to safely guide ships home.

Talk with local history buffs at museums and landmarks like these.

Visit the many mom and pop restaurants, bars and businesses where locals can tell you a thing or two.

See 35 murals depicting local history and learn more at the Superior Public Library.

Get out there to discover a living connection to the past on the trails and waterways that generations have traveled.